Jun

MICA’s Social Design Exchange | Low-income Housing is a Home

[responsivevoice_button voice=”UK English Female” buttontext=”Listen to Post”]

Last May, I watched 12 graduates from the Maryland Institute of College of Art’s (MICA) Master of Art’s in Social Design (MASD) program present their final theses. Problems ranged from cleaning the Jones River Falls, to the reintegration of community members who return from the prison system. They were all so inspiring. I find myself increasingly interested in the social contexts to design, and these resources are incredibly important. They create a dialogue where visual designers have none. They cultivate solutions beyond the tactile and applied arts. But they also provoke tastemakers and cultural influencers to think about their messages.

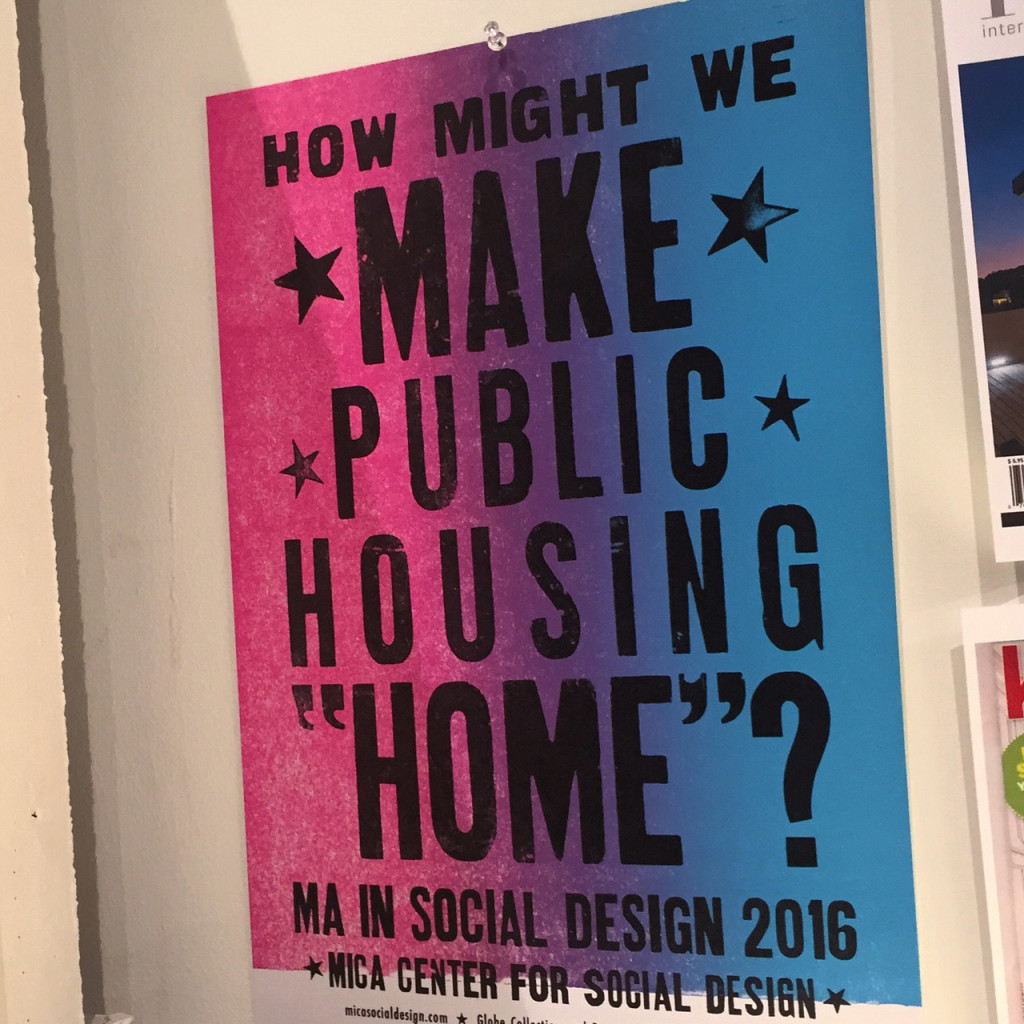

Making public housing a home

Diamond James, previously interviewed in Black in Design @MICA, chose to focus her thesis on public housing.

Reading in the Bathroom: Design Sponge* at Home

After visiting neighborhood public housing, and taking in feedback from residents, she concluded that everyone designs their homes. Therefore, they should have a say in how they want to improve their living conditions.

As designers who work in publishing, interior design, industrial design, marketing, advertising, particularly lifestyle marketing, we think we’re reaching one specific market. The truth is that how we market a beautiful home also reaches those in public housing. We can decorate and adorn our homes as we see fit, regardless of income or background. But even as I carefully adorn my own apartment, I am disempowered by my living situation.

”I have seen and felt the encroachment of gentrification, something I have both conspired in and victimized by.

To be a black gentrifier in low-income housing

This is my home.

I love my home so much, that over the past 11 years, I have captured its iterations. It reveals my love of color, food, and empty glass bottles. As my income has improved, so has the adornment of my home. A cheap loveseat and mattress bought at a clearance store were now replaced with a custom leather sofa and handmade mattress from mid-century modern furniture houses. Bookshelves that barely held together are now topped with bookends from an irreverent-yet-commercial sculpture. And curios from my travels around the world dot my humble home.

Yet, these are the areas that often characterize my neighbors and I:

These are the common areas of the building: Hallways, entrances, and laundry rooms. So-called guests of others have been known to assault residents, have sex, do drugs, and defecate in these areas. Residents do our best to maintain them when building management cannot or will not.

”As designers who work in publishing, interior design, industrial design, marketing, advertising, particularly lifestyle marketing, we think we're reaching one specific market.The truth is that how we market a beautiful home also reaches those in public housing.

My home has been a respite while I design an annual report, repaint a wall, repurpose outdoor furniture, or build a CMS (content management system). It has kept me thriving by continuing to stay in the center of the city. It keeps me connected to my very hardworking, lively, funny, diverse, caring, proud, outspoken neighbors. But it has also been mis-recognized — Section 8 housing, the ghetto, crack houses — and all the stigmas that come with those assertions. Regardless of description, as long as we have a place to lay our heads, we have a right to call it a home.

While the neighborhood as a whole is considered very desirable, my apartment building — despite its prime location — has become a place where very few young, white twenty-somethings would want to live (despite their own low incomes). Nor is it considered valuable when mostly black, and Latino people live there. And this is important for several reasons.

I am stunned at how if a critical mass of white bodies come into the neighborhood, resources magically show up: New grocery stores! A dry cleaner! Organic markets! Hip, new bars and restaurants! Yet the black and brown bodies who have invested time and money for generations, have been routinely overlooked. It’s assumed we don’t want nice things. Diamond’s work, along with others from the Social Design Exchange are disproving this assumption.

City Lab: How Black Gentrifiers Have Affected the Perception of Chicago’s Changing Neighborhoods

I have seen and felt the encroachment of gentrification, something I have conspired in and have been victimized by.

I have to reconcile with what it feels like to be a gentrifier, but not be seen as such because I’m black. I’m the one shopping at organic markets, patronizing pop-up shops, boutiques, attending whiskey tastings, coffee shops, and craft cocktail spots. And I still see the looks of contempt from young white faces in the neighborhood. I still hear the question, “So are you from here?” Rather than, “Where are you from?”

The Social Design Exchange intends to share problems, solutions, and insight. As a community member, it would have been a disservice to recount this presentation and only talk about that.