Mar

I Take It Back, Prince Would Not Have Been Okay With Pantone’s Color Of The Year

[responsivevoice_button voice=”UK English Female” buttontext=”Listen to Post”]

I was catching up on Season 4 of Fox’s Empire when this happened. (Click below to see/hear a video clip of a performance of “Let’s Go Crazy” on the TV series.)

Empire’s “Let’s Go Crazy” sequence. The last time I saw this many Black characters on a primetime network television show take very Black music and still manage to look this corny, I was watching the Huxtables lip sync to Ray Charles. A family of talented Black performers and musicians singing and costumed as Prince at a kid’s party? Because the child’s name is — wait for it — Princess?

”Prince's real brand was his unique way of creating value in everything he did by making experiences personal, intimate, and worth paying for.

As I’ve said before on this blog, I’m not the Fun Police. I get people want to enjoy things. But there’s a reason that for many years we never saw such easy co-option of Prince’s music and persona by another entity. It’s off-brand.

Pimping Prince to Sell Anything

When Prince Rogers Nelson died unexpectedly in April 2016, many were surprised to find he never had a will. Prince was notoriously protective of his music and his intellectual property. Now, his family manages his estate. Almost anyone, with permission from his estate, has access to commercialize Prince’s brand and claim an homage. Including Pantone.

Every year, the color-matching company declares a Color of The Year. As such, Ultra Violet 18-3838 ostensibly suggests how designers and tastemakers use it to brand anything from a pair of shoes to a pair of headphones. But this year the company tied itself to Prince’s legacy.

The Minnesota Twins are creating Prince merchandise. Even AIGA participated in the Prince-themed hustle for its 2017 national design conference because it was in Minneapolis.

I’ll admit to falling for this. As soon as the color was announced last year, I pitched an idea to a fellow designer: Pick a key date in Prince’s life, and interview chapter members on their best memories of his work. Then feature them in a photo spread styled in tones based on Ultra Violet.

I was wrong. That is a horrible idea. Here’s why.

The (Real) Evolution of Prince

Most Prince fans are familiar with his most popular work, the soundtrack and movie Purple Rain. But after the critical and commercial failure of Under The Cherry Moon, a lot of people gave up on Prince. Like David Bowie‘s Ziggy Stardust era, many fans only remember an artist at their most famous, and immediately attribute that to their best work. But it’s those who stuck around, curious about how a music genius does (or doesn’t) evolve, that continue to define their legacies.

A “Brand” Can Also Be A Person’s Values

Prince’s real brand was his unique way of creating value in everything he did by making experiences personal, intimate, and worth paying for. From his public fight with his record label to own his masters, to the brilliant legal strategy of changing his name to a symbol, he was intentionally working to protect the value of what he made.

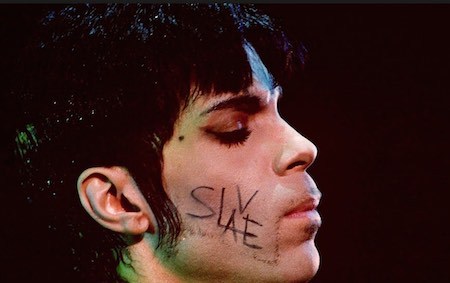

In 1993, Prince famously wrote the word “slave” on his face in public protest of his then-record label Warner Bros, owning his masters.

His other unique quality was how he made people feel when they encountered him. Almost everyone has a Prince story. I never had the honor of meeting him or seeing him live. But about 5 or 6 years ago, I was coming home from partying. It was about 1 am, and I was still a little tipsy. I turned on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, and Prince was performing with new latest band 3rdeyegirl. They were incredible. Toward the end, Prince laid down this amazing solo. Then, in true form, he hurled his electric guitar over his head, smashed it into pieces, then walked off stage while his band kept playing.

This was 2012-2013 when artists then and still are easily downloadable and shareable with little to no compensation to them as creators. In an era when people’s careers are made or revived by going viral, Prince was still in control of his brand. You would’ve never seen a clip of that moment on YouTube or NBC Universal the next day. For a window of time, well into the 21st century, the only people who could claim they ever saw that is if you were a guest in the audience, a Late Night staff member, or if you were like me: up late and turned on a television.

”Like Ettore Sottsass was to The Memphis Style, Prince's relationship to his purple-themed, Purple Rain period was very short-lived relative to the rest of career.

While he warmed to the use of social media and the use of his memes, he never lost control of the narrative. If R&B producer/performer Lil’ Mo complained that Prince’s bodyguard wouldn’t let her into the bathroom during Essence Festival, with one tweet — I hope she know, none of her clothes match — he could reestablish one of his main operating guidelines: No matter what you think of him, he was the petty bitch in the situation. And you’ll just have to live with it.

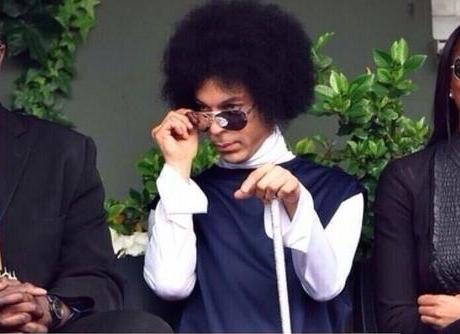

Prince could cut you down with a single side-eye if he thought you were trying to do a version of him, rather than trying to do the best version of yourself.

- This was at the 2010 BET Awards, featuring a tribute to Prince.

- When Patti LaBelle kicked off her shoes, he caught one in mid-air.

That was Prince.

His brand was not a color. Like Ettore Sottsass was to The Memphis Style, Prince’s relationship to his purple-themed, Purple Rain period was very short-lived relative to the rest of career. While some our intentions seem to come from the right place of loving an icon, in many ways we’re not really honoring him because we only see him as an icon. We trapped him in time without asking ourselves if Prince thought it was okay.