May

I Feel Bad for Rachel Dolezal. She Still Makes Bad Art.

[responsivevoice_button voice=”UK English Female” buttontext=”Listen to Post”]

I finally watched The Rachel Divide on Netflix. It’s about Rachel Dolezal who infamously convinced people she was Black when in fact she was born White. I came away from the documentary feeling bad for her, because of her abusive childhood. Childhood trauma is not a joke and should be addressed with a qualified professional.

But she still makes bad art.

”In Rachel's mind, there is no space where Black lives are joyful, humorous, awkward, passionate, or abstract. Nor does she see us as her intellectually-creative peers, but simply objects of desire that must be saved.

When her story first broke and it was revealed Dolezal went to Howard University, which was around the time I was a student in their graphic design program. This was before her current appearance, but either way she likely would have stood out. The fine arts program takes up only one floor in Childers Hall, and the graduate program is even smaller. Maybe it’s because we were too busy building our own portfolios to be bothered with this ridiculously pretentious person (which is saying a lot for an art school), but none of us recall ever crossing paths with Dolezal.

She later sued the head of the fine art department Alfred F. Smith over claims of racial discrimination. Aside from being then-chair of the art department, Al Smith was my drawing teacher. I was also taught by artists Kebedech Tekleab and Edgar Sorrells-Adewale (now retired). All of them unquestioned masters in their fields. My art professors at Howard were not just technically proficient. They were brilliant thinkers of art criticism. They understood nuances in Black aesthetics. They encouraged outsider thinking but doing so with an authentic purpose. That, I think, Dolezal couldn’t handle. Her simplistic takes on the Black experience were not enough. She thought her mediocrity would fly at a Black school. So in 2002, she pulled an Abigail Fisher.

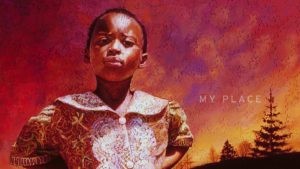

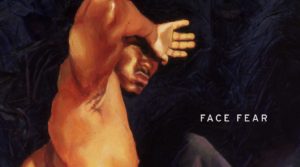

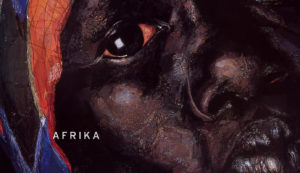

While Dolezal shows some technical proficiency, she is incredibly lacking in her proficiency of the Black experience. Not because she is White. I too had White art professors whose subject matters were not reductive of the Black experience. The biggest misconception Dolezal has of the African American experience is one from a place of constant struggle, oppression, prideful stoicism, and marginalization. In Rachel’s mind, there is no space where Black lives are joyful, humorous, awkward, passionate, or abstract. Nor does she see us as her intellectually-creative peers, but simply objects of desire that must be saved.

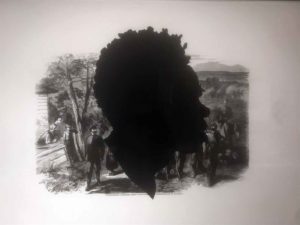

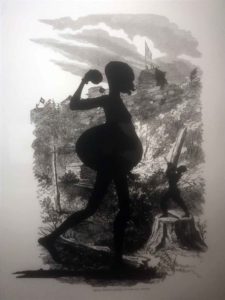

Comparably, I think of the artist Kara Walker. Walker, who uses themes of the Antebellum South to reveal contradictions within the one-sided slave narrative, also reveals a bit of her personality. In Kara Walker’s work, we see an eccentric irreverence toward taboo subjects. She does not simply pity the suffering. She uses history to explain who caused the suffering why the suffering happened. As much as Walker uses institutional racism and racialized bodies to work through her personal issues, she is more than someone interested in using Black bodies to project her pain.

Just as Dolezal’s social justice work seemed well-intentioned, but ultimately designed to be a projection of her personal pain and trauma, so is too her art. She grafts her legitimate child abuse onto the African American slave narrative and thinks it’s synonymous enough to own.

”In Kara Walker's work, we see an eccentric irreverence toward taboo subjects. She does not simply pity the suffering. She uses history to explain who caused the suffering why the suffering happened.

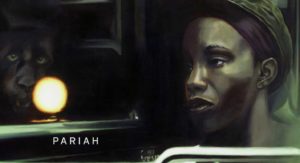

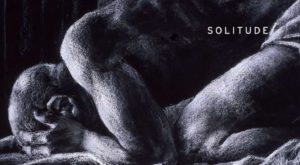

Dolezal’s strongest piece may be the last one see toward the end of the documentary. Throughout The Rachel Divide, we see Dolezal working on a self-portrait. In it, her skin is darkened with self-tanner. She wears an African-inspired chest piece. And she wears her hair in a headwrap.

But during a hyperspeed cut of her progress, we see Dolezal break down in tears. A woman unclear of who she is. We’re left with this final rendering.

Honest. Self-reflective. Self-aware. I don’t know if this is good art. But it’s a good place to start.

© Netflix. All rights reserved.