Jun

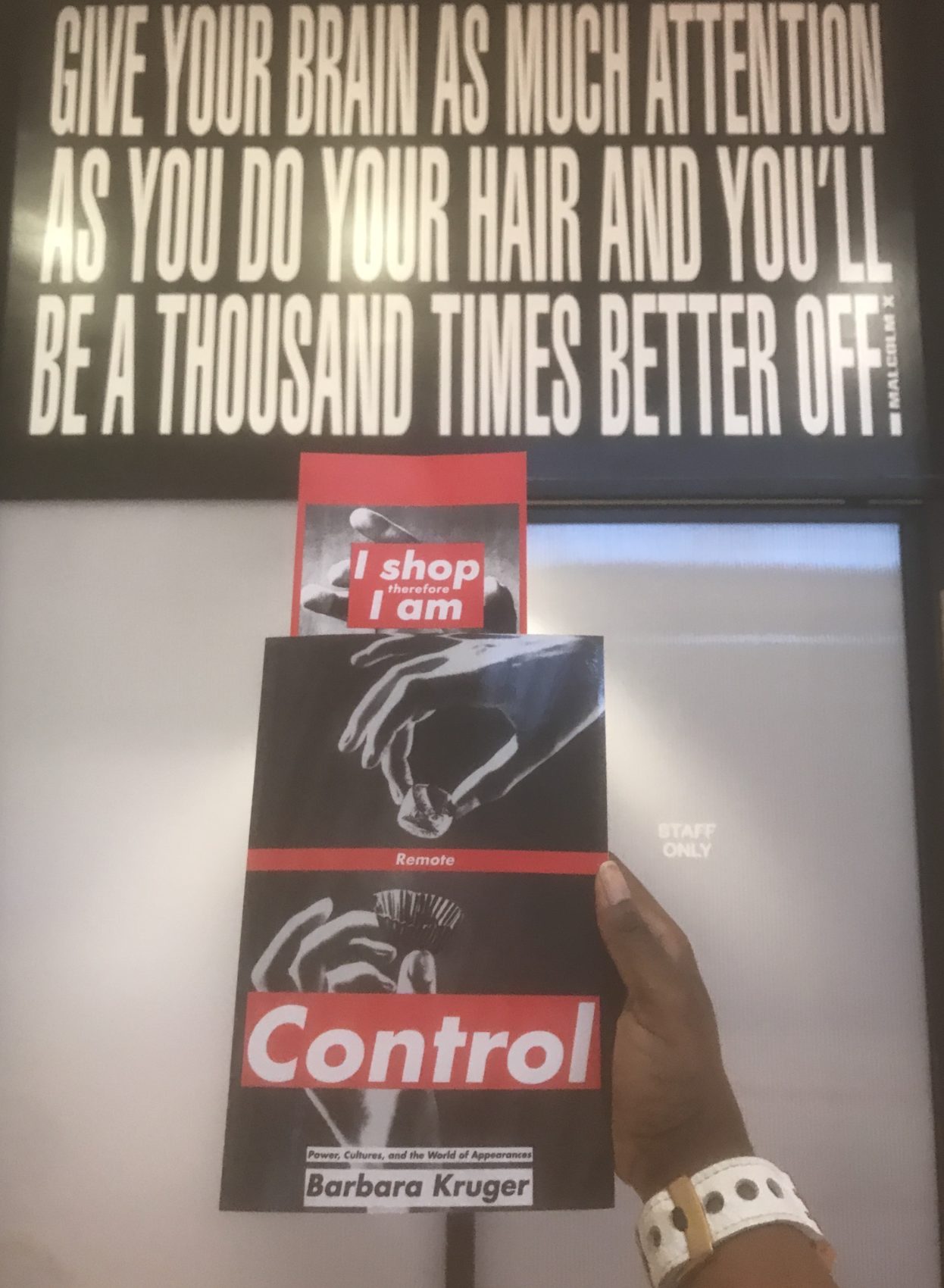

Reading in the Bathroom | Remote Control: Power, Culture, and The World of Appearances

[responsivevoice_button voice=”UK English Female” buttontext=”Listen to Post”]

When I began design writing a few years ago, I knew that I was walking along a rather shallow, but nonetheless existent path. I knew there were women graphic designers and artists who wrote sharply about design, culture, politics, and feminism, while still keeping their day jobs. They were paid to write about film and television with an unflinching perspective. When you’re walking on a path like that, you don’t know whose footsteps you’re following, but you know they’re there. When reading the literary work of artist and graphic Barbara Kruger, I finally knew whose steps I was following.

Barbara Kruger is most well-known her subversive, large-scale, type-driven art installations. She’s also known to have expertly clap-backed at douchebag brand Supreme for having the gall to sue her for copyright infringement after using her work as a source of inspiration.

”I knew there were women graphic designers and artists who wrote sharply about design, culture, politics, and feminism, while still keeping their day jobs.

Remote Control: Power, Culture, and the World of Appearances is a collection of essays and one script treatment, all written by Kruger. Spanning the early 1980s through early 1990s, Kruger critiques television and film and the impacts they have on us. What makes her perspective unique from a social scientist is that she thinks now like a maker of products. Kruger critiques television and film as objects happening to us. With that frame of mind, she often writes that are hilarious, pointed, absurd. Take for example this excerpt from a September 1987 essay on television coverage of the Iran-Contra scandal:

Accordingly, three decades after the Army-McCarthy “hearings” we do ourselves glued to the Irangate “seeings.” Ollie North, like Ronald Reagan, is a triumph of the rhetoric of the image, tucking all unpleasant textualities behind a glazed and hunky pose that handily evacuates the specificities of the seemingly real.

She takes sharp aim at how television shows like The Home Shopping Club and The Today Show promote a facade of familiar places like home, but can ultimately be very alienating, as she does in her January 1987 and 1988 essays.

Where her aim hurts a bit is at Saturday morning programming Pee-Wee’s Playhouse and The Muppet Babies. When it comes to morning and evening news, her barbs seem like a fair fight because the target audience is adult programming and by extension adults. But when it comes to children’s programming, it’s like she’s kicking puppies.

”What makes her perspective unique from a social scientist is that she thinks now like a maker of products. Kruger critiques television and film as objects happening to us.

I’ll admit to having grown up with Saturday morning kids’ show faves, so maybe I’m a little biased. But I also grew up in the era when artists like Kruger were teaching the public how to be critical of the stuff they were watching. While Kruger was compelling more thoughtful readers to consider the implications of Pee-Wee’s fetishization of things (as she does in her March 1987 essay), my mother astutely pointed out, even when I was young, that Pee-Wee’s Playhouse was the only Saturday morning kid’s show that had three Black cast members. Casting Larry Fishburne as Cowboy Curtis, S. Epatha Merkerson as mail carrier Reba, and Gilbert Lewis as the King of Cartoons is still subversive. My mother suspects that is the reason why Paul Reubens (who plays Herman) was targeted and arrested for indecency in 1991. I bring that pointed, unique perspective to my cultural criticism because women like Barbara Kruger taught me how.

Where I struggle the most with this collection is her collection of film reviews. Unlike the first half which mostly covers television, Kruger smartly skewers well-known properties of pop culture. Radio show shock jock Howard Stern, Michael Mann, and Miami Vice, Kirk Cameron and Growing Pains. But when we get to film, she’s raging against the machine and pointing to movies that have gone on to become so obscure, it’s hard to care what the outrage is about. As an art house film fan, I am digging deep to care about the larger social implications of The Man Who Envied Women, Madam Satan, and Indentificazione di una Donna, and I struggle.

I take Kruger’s written work within Remote Control as both as a source of inspiration and as a warning. Never be afraid to say what needs to be said. But be careful about how fine you sharpen your focus at what or who you are targeting. If everything is worth being outraged about, then years later, nothing is.

Reading in the Bathroom is a book review series by IDSL. Reading is obviously not done in the bathroom exclusively. Sometimes it’s on a park bench, outdoor cafe, or on the train. But the best reading is done in the bathroom.